I got recently asked about the plaques in Ch’ien-lung, and whether they were important and why — the mudras (finger positions) were tossed in for good measure.

Below is the question followed by the response.

Thank you for your inquiry. These are good questions.

I do mention the reason for the plaque work and by extension for the mudras in a few places in the book — among others, Appendix A on alternate nostril breathing — but re-reading it, I can see it is a little dense to unpack. Ah well, that’s what the second book is for…

Allow me to be a little more clear and accessible.

The plaque work is pretty important to the internal work of Ch’ien-lung. Each particular plaque has a combination of colors and shapes to symbolize a particular Animal mindset. So it has innate meaning, like most mandalas, and that can add value by itself. In addition, the plaque provides a focal point in meditation, where the symbolism of the shapes and colors by-passes your noisy linear mind and appeals to the bigger sub- and unconscious aspects of who you are.

The plaque work involves 1) focusing on a plaque, while 2) doing a breathing pattern, while 3) embodying the Animal, while 4) running energy along the Animal circuit.

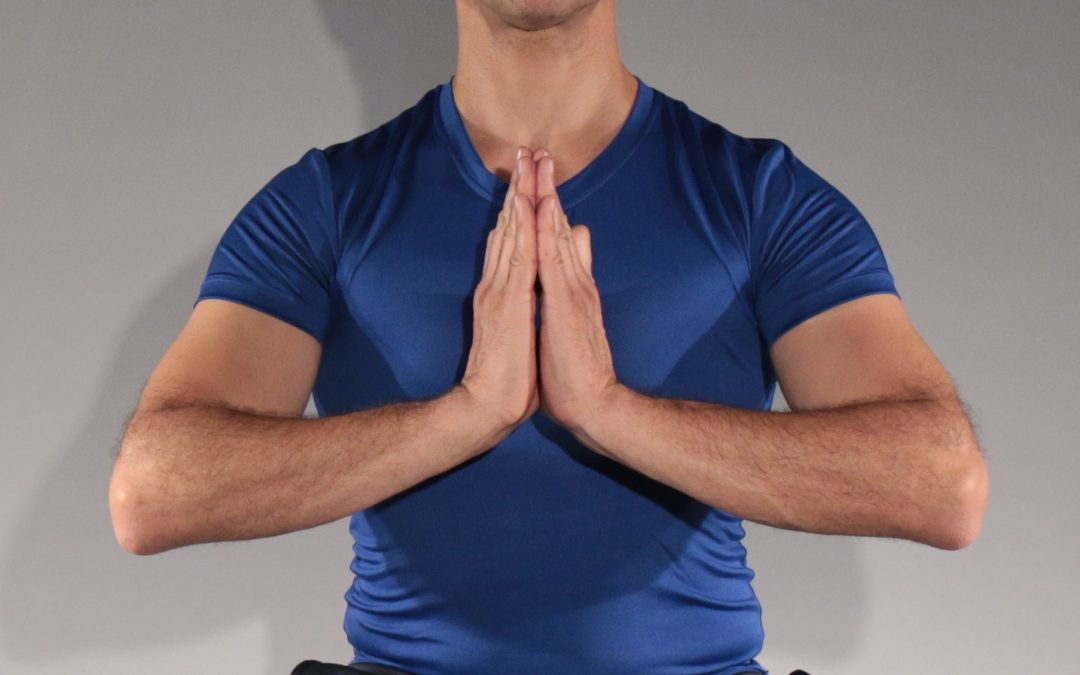

The alternate nostril breathing with the plaque is a “box-breathing” or variation, along with holding the mudra in one hand, while seated in a particular asana, and using the other hand to pinch your nostrils close. Yep, it’s involved. You can think of all of this stuff as the part where you practice “doing an external action.”

While you do the alternate nostril with its involved counting, you also adopt the Animal attitude. It’s subtle, and it’s a little like doing a meditation in role-play, but it’s also the purest of embodiment of the archetype. You can think of this as the part where you practice “doing an internal action.” The action here is being, that is, actively choosing to be a certain way.

So, far we have two parts: External doing versus internal being. Make sense?

But wait! … There’s more!

You are also shifting your focus along the edges of the shapes, doing so in-time with the rhythmic breathing. For example, your gaze follows the edge of the triangle as you inhale then hold your breath and exhale. Your gaze follows the perimeter of the triangle or circle, with your focus cutting the edge like a laser in a James Bond movie (“No Mr. Bond, I expect you to die!”). You can think of this part as where you practice “control of your external focus.”

While doing this, you are also using your attention (kind of like a magnet) to guide energy along circuits of the body. You can run energy up and down your spine for Cobra, you can run it around the groin and belly for Panther. There are different circuits for each Animal. You can think of this as the part where you are practicing”control of your internal focus.”

So, the reason the plaque exercise is important is because you are exercising how to act and how to be while focusing inwardly and outwardly. All at the same time. Very simple, but challenging. It’s a tall order, one that is designed to stretch you out of your comfort zone in a very fundamental way.

Your second question is about the mudras and their relevance. Well, first, as a cognitive psychologist, I can tell you, the mind dedicates a great deal of attention to the hands — where they are now, what they are doing, where they are going, etc. processing all that informationis all automatic, and it’s computationally massively heavy, and all that processing happens with seeming ease. So, to account and include at least a little of that potential for attention, we use the mudras in the meditation.

You don’t have to stop at the hands, of course. You can do something similar with each of the senses. You can give yourself something to imagine seeing, hearing, tasting, and smelling for each of the Animals — in fact, that’s part of the Warrior Exercise in Appendix D. The idea is that you occupy the channels of attention to each of these modalities of perception. In so doing, you are being thorough in your practice of quieting the mind — actively ‘erasing each track’ of attention.

The second reason is that, as you advance in your practice, the mudras can trigger the Animal. Imagine you have been practicing the Animals and their mudras for a while. You do the Animal bow, and then finish with the mudras. You do this every day for a week or so. You give it a sincere and genuine dedicated focus. You’re having fun, enjoying an added dimension to your day. Then one day as you walk along, minding your errands, for fun you do the Animal mudras. Click. All of a sudden your body shifts posture, your ears prick up, your eyes hone in, your body moves differently, all in line with the Animal work you have been doing. The association between the mudras and the Animal is strong. It has a momentum of its own, so that now you can use the mudras like a tool in your practice of the Animal, and reinforce the Animal in situations when you want to embody it more.

As a cognitive psychologist, the phrase I would use is ‘the mudras can be used to prime the Animal.’ We talk about priming in relation to memory, where to prime your memory means to ready a memory to fire. After a period of exploring in an Animal, building thousands of associations about the Animal — its breath, focus, interests, postures and, yes, the mudras — just making the finger position primes and readies firing of all of those associations about the Animal you have built up.

I hope that answers a little more clearly what the mudras and the plaques are about.

If you are like me and in quarantine these days, I am happy to do a zoom or phone session with you if you have further questions.

cheers!